Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How Lobotomy Corporation teaches the value of bad choices

Decision making in videogames is obviously an important aspect of player engagement, but for today's post, I want to talk about how the game Lobotomy Corporation was designed around making the player choose between all the bad options.

After finishing Library of Ruina I decided to go back and play Project Moon’s first game: Lobotomy Corporation. Both games couldn’t be further apart in terms of design despite being connected with the story. Lobotomy Corporation is a harder game to recommend, but it does present an interesting conversation about choice — and how making the player pick their poison can be a crazy experience.

Running an SCP

Lobotomy Corporation is the first game story-wise from Project Moon (I already covered my thoughts on Library of Ruina in another piece). Here, your job is to manage a corporation that houses all manner of creatures known as abnormalities with the goal to extract enough energy out of them daily to meet your quota.

All this is told through a very dark story filtered through cute little chibi characters to hide all the horror. What separates Lobotomy Corporation from other games I’ve played is that you are fashioning your own nightmare experience when playing the game.

Bad News or Worse News?

The beauty and nightmare of Lobotomy Corporation come down to one simple fact — every choice you make is bad and will come back to haunt you. Every few days, you are required to choose another abnormality to keep in your facility. When you start playing the game, you won’t have any idea what‘s what, but finishing their lore entries will stay persistent over different plays.

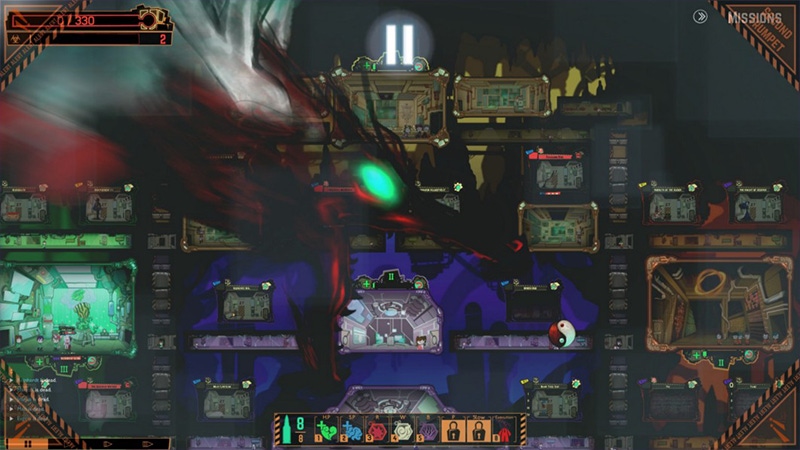

The abnormalities come in all shapes and sizes and range from cute little knick-knacks that could be the star of a Disney channel Halloween movie, all the way to Lovecraftian threats that will destroy everything if they get out…which they will. To add to the danger, after you have worked with a specific number each day, you’ll trigger a meltdown event — either requiring you to quickly interact with containment units or deal with a randomly chosen invasion in your base.

Just one of the many things that can kill everyone if you’re not paying attention

Even when you know exactly which abnormalities you’re choosing from, that doesn’t keep you from picking the most dangerous ones. The reasons are:

The more dangerous abnormalities give you more energy allowing you to speed through the day and deal with fewer meltdowns.

They can also have higher-tier equipment unlocks, allowing your characters to better survive and dish out damage compared to low-rank gear, a necessity in the back half of the game

Completing the game all the way will require you to learn everything about the abnormalities and complete specific side quests whose difficulty will be dependent on the abnormalities chosen

In one play, I thought I was taking an easy abnormality until I realize that I installed a two-minute timer that if I don’t keep checking will summon the “death train” to kill my people, and that’s still on the lighter side of threats. Then later, I put in a creature who will cause a slime monster plague as I try to work with it. And then further still, I put in something that causes trouble after every five interactions with other abnormalities, including a certain death timer I just mentioned. No one abnormality (except for the hardest) is that difficult to deal with, but it’s the combination that will frame your experience with the game. An abnormality that activates when people die doesn’t sound bad if you know what you’re doing but combined with one that goes on a murder spree the second it gets out is a very nasty combo.

Every decision you’re going to make in Lobotomy Corporation is inherently going to make things worse for you, and that is a rare sight for a game. In a way, it’s the opposite style of what I talked about in games like Monster Train and Slay the Spire in which the player is deciding what cards they want to add to their deck to make it better. Either way, the player is the one in control over their destiny, one side is just more aggressive at it than the other.

Making Controlled Choices

Gamers have been talking about random number generation or RNG for years to describe how the game itself can define your fate: Missing a shot in XCOM, getting an ultra-rare character in a gacha game, and many more examples.

The problem with a lot of choices and rewards is that they are random: a game could give you the very best, or very worst, option and there’s no input by the player. A concept that I’ve been talking about in videos and during our Game-Wisdom streams is the idea of a more controlled form of RNG. I don’t know if this term will stick, but I’ve been saying “controlled number generation” or CNG.

The idea is that the player is the one who is deciding the outcome of rewards and situations; not just being give a good or bad result. Going back to my piece I just wrote about feedback when it comes to learning a game, the player is not being told what option is good, bad, or ugly, but is given the knowledge as to what these choices mean.

It’s all fun and games until the death train rolls in

You rarely want to have something that is always good or always bad, unless you’re looking for “spikes” in your design, but the concept is that the value of a choice is dependent on what is happening in the game. Think of this as designing your game around sidegrade choices — giving the player something good at the cost of potentially something bad. Every choice has the potential of value during a run, but that value is not fixed. If I’m using magic damage in an RPG and I have to choose a curse and pick “all melee damage reduced by 50%,” that means nothing to me during that run. However, that could be disastrous if on another play I’m building a warrior character.

Learning Lobotomy Corporation

Lobotomy Corporation is one of those games that you’re not going to find anyone else with a game similar to it, and that alone makes it worth checking out. While it is not the most accessible or approachable game (there is one abnormality that will crash your game on purpose if you use it), it is still a great example of how letting the player choose their successes, or failures lead to fulfilling gameplay and letting them be the masters of their own fate.

If you enjoyed this story, consider joining the Game-Wisdom discord channel. It’s open to everyone.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)