May 30, 2024

Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren’t really that simple at all.

Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren’t really that simple at all.

Earlier installments cover topics such as how Techland centered player feedback in the development of Dying Light 2, how the developers of Insurgency created the architecture for console crossplay, and how League of Geeks created a complex asynchronous multiplayer in Solium Infernum.

In this edition, we learn how Double Dagger Studio created the perfect cat animations by shifting away from realism and embracing a more stylized approach.

Hello, I am Micah Breitweiser, an animator at Double Dagger Studio working on the game Little Kitty, Big City, Little Kitty, a game where you play as a cat, made by people who love cats, for people who also love cats. Affection for cats was the essential building block for everything we did, from the concept art to the adorable character designs to everything that would come after. When I joined the project in early development, the game was still finding its shape, but the core idea—having an iconically cat experience—never changed. As an animator, I’m a little obsessed with movement, and as a lifetime cat lover, I’m particularly obsessed with how cats move. I knew our audience would want to recognize their own cats in our little kitty, but as I would come to find, that didn’t get us far enough. This game needed to be delightful, and for that to work, we couldn’t just portray a cat in motion.

While that’s simple to recognize in hindsight, bringing Kitty to life was a long and collaborative process. Especially on a project like a video game, finding what “works” can often be a counterintuitive cycle of adjust-and-assess, one that only ends when people are finally able to say “yeah, that’s better” with enough satisfaction to end the discourse. Finding a creative goalpost is essential. Once you know where you’re headed, you choose the techniques that will serve you best in getting there. The first step was to find answers to key questions about our little kitty. We wanted the animation to be a high-quality, essential part of the game, but we didn’t know exactly what that meant yet. Kitty’s animation started to come together through trial and error, as we worked toward defining what an iconically cat experience actually meant in practice, led by the game’s creator and lead designer, Matt T. Wood.

In early development, Kitty wasn’t our kitty yet, just a store-bought asset with some rudimentary functions (walk, run, idle, etc), and we had lots of defining to do. We knew the animals in the game would speak, but how expressive should Kitty be? Our creative questions always circled the core principle of delivering a definitively cat-like experience, so players should feel as if Kitty is a somewhat standard, representative cat. That put us in realistic territory, more or less. Our character designer and modeling artist, Valentina Hawes, delivered an adorable kitty model that not only suited that purpose well but had a charm I instantly latched on to. Features like luminously large green eyes and rounded mitten-y feet nudged me in an anthropomorphic direction, but as animation work started, I was hesitant about personifying Kitty too much. I took a straightforward, blank-slate avatar approach. Those animations were standard, representative cat movements. I was doing basic locomotions then, so as the in-game kitty gained more functionality, we got a better feel for how the player would be experiencing our kitty. Unfortunately, it wasn’t quite working. The movements were realistic, but that was part of the problem. Kitty felt a bit bland. Matt eventually mentioned that Kitty should feel younger and clumsier.

As I considered that, I realized how many opportunities to elevate the game I had missed. Little Kitty, Big City was already shaping up to be a game about intrinsic rewards, where objectives included things like hopping inside cardboard boxes and knocking glass jars off of shelves: tactilely engaging, iconic cat behaviors. The animation wasn’t uplifting these gameplay objectives. It was lacking that sense of delight. I started thinking about how to make movement itself a special experience. What if jumping in a box or crawling in a hole was so appealing that you wanted to do it again, just to watch a cat move? Easier said than done, as “appealing,” though a lovely idea, is a woefully inadequate creative goalpost. I needed specifics. What about the way cats move appeals to people? And how can we best portray those aspects in the game? If you were a cat, what would be the best part?

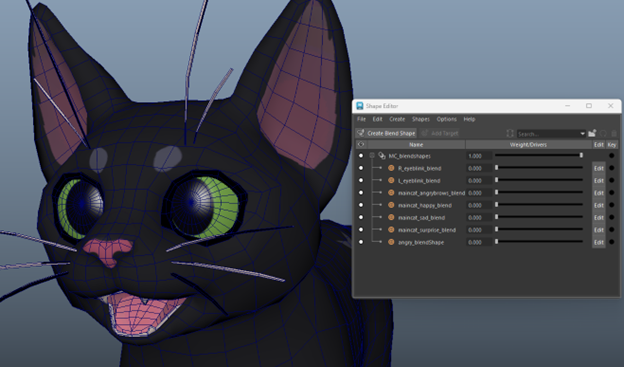

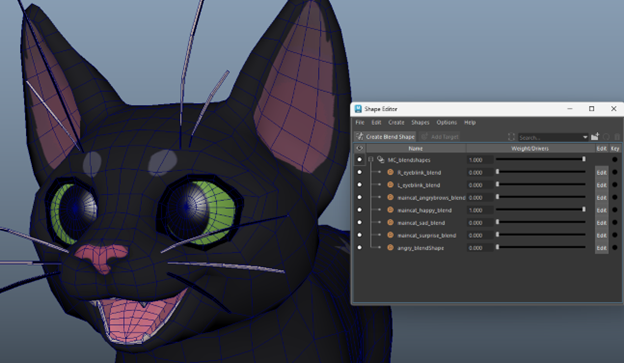

We needed a livelier kitty, and one way to do that was to dial up the anthropomorphism. Matt suggested I give Kitty the ability to make facial expressions. Our animation rig was very minimalistic, just a mesh, a skeleton, and some foot IK. I wanted to push the personality and animation quality, but getting fancy with the rig wasn’t an option, so I set up blend shapes. If you’re familiar with rigging, then you know this is as basic as it gets. You duplicate your mesh, edit the duplicate into a shape (in this case, a smile), and then you have a slider that works like a dimmer switch on a lightbulb, turning the deformation on and off.

Images via Double Dagger Studio.

This setup was limited. On fancier rigs, you can select part of the face and move it however you want, whereas we could only turn a shape on and off. But this restriction was ultimately helpful. It limited Kitty’s anthropomorphic capability to basic expressions: happiness, sadness, surprise, and anger. It created the unspoken rule that Kitty doesn’t do complex emotions and it helped me find the sweet spot for personifying our kitty. It wasn’t realistic, but making human faces gave Kitty a sense of internality. Kitty now had thoughts, and would be reacting to the world around them, which fostered the sense of discovery we wanted players to feel. Still, to be authentically cat-like, Kitty’s body would have to be much more expressive.

To that end, I thought harder about the things I personally love the most about feline locomotion. Cats are an animator’s dream because they’re arguably the most dynamic creatures on earth. They can curl into nebulous furry blobs or leap and twist into complex shapes. They can be the most graceful thing you’ve ever seen or flail wildly when they slip off your kitchen counter. Their range is immense. As we honed in on some of our favorite cat behaviors to include in the game, some funny, some clumsy, some graceful, I looked for ways to make them more special. Personally, my favorite thing about cats has always been their fluidity. That was a unifying principle that felt iconically cat-like to me. I figured that no matter what Kitty would be doing, clumsy or otherwise, I’d make each shape fluid from nose to tail.

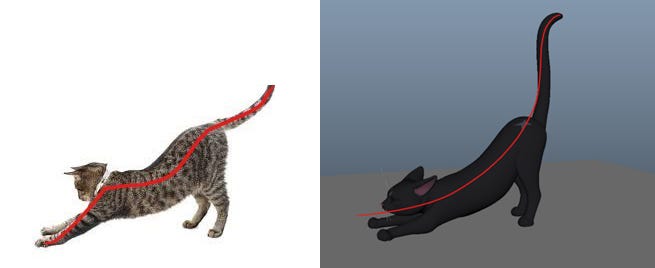

Animators talk a lot about "line of action" in posing characters, which was essential here. Basically, you create a singular rhythm that moves through the shape of the whole body. This technique has infinite applications, but for Kitty, I used smooth, undulating curves. It’s not necessarily realistic; it’s a subtle abstraction. Real cats have great rhythm to them already, but our kitty is simpler.

Image via Double Dagger Studio.

I reworked many of the animations I had already done, adding this smooth rhythm to each pose. Bit by bit, Kitty’s motions started to feel harmonious in-game, with a lot of help from Matt, who created the animation states and blended Kitty from state to state (and probably did a lot more work than I’m even aware of). It was a collaborative process, but as we identified behaviors people would enjoy seeing, and I stylized them to reflect what I liked most about cats, moving through the game became its own reward.

Collecting hats became a whimsical moment where Kitty breaks into playtime, wiggling and batting the orb around, lighting up with curiosity when the orb breaks open.

When hopping into cardboard boxes, Kitty is uncoordinated but maintains the sinuous lines that keep the movement fresh and fun to watch.

Of course, cats in motion are a lot more complicated than iconic poses. The way a creature moves through the poses is equally important. The speed, the path a body part takes—it’s all integral. Observing real cats in action is the only way to fully understand how all the elements of their locomotion coalesce. To study them, I stepped through reference videos, frame by frame, making close observations. If the cat’s body goes left, where does the tail go? If the cat looks right, do the ears move first? (They do!) Noticing these things is fundamental for a realistic result.

That said, real-life reference can only take you so far. Our intro sequence, in particular, welcomed even more cartoony elements to the game, and it’s an apt representation of this problem. How do you depict something like a cat riding on the back of a crow, believably?

Since I obviously couldn’t get reference footage of this, I reflected on all the live references I’d studied up to that point. I posed the character intuitively, adjusting and assessing based on what I knew. Cats had been my primary subject for a couple of years at that point, and I trusted my internal reference library. As I worked through the sequence, I looked for opportunities to exaggerate the fluidity and personality in Kitty’s motions. I tried to keep Kitty’s facial expressions as big as the rig allowed and as visible as possible. For each pose, I worked the shapes into pleasing curves, suggesting a slinky, flowy rhythm. I also had some fun breaking this rule for one particular pose, using a jagged line as punctuation for Kitty’s frazzled moment.

Image via Double Dagger Studio.

Cats may not usually put their tails into these sharp angles, but I found it funny and fitting here. Challenges like this divulge the constraints of realism; alone, it couldn’t have delivered the iconic cat experience we were looking for.

Bringing Kitty to life revealed a fun paradox; as we added anthropomorphic elements and layers of abstraction to the animation, Kitty began to feel more realistic, not less. This discovery happened organically, and by the time we were ready to ship, Kitty had made the transition from a generic cat avatar to our little kitty character: naive, clumsy, obliviously mischievous, and a huge goofball. Kitty the cat came from the reference, but Kitty the character came from all the ways we left that behind. As important as it is to study natural references, it’s equally important to step away and digest what you’ve seen, starting from a blank slate with your imagination at the forefront. In other words, it’s important to animate subjectively.

However, achieving this subjectivity isn’t possible without the hand-keyed animation process. It creates yet another avenue, among many, for human creativity to be part of the gaming experience. It’s another point of view, an opportunity for both substance and style. Hand-keyed animation can be slow and expensive, especially for indie projects, so I have the open and iterative approach Matt created at Double Dagger Studios to thank for the final result. This team appreciated the hand-keyed process and supported me with the budget and time I needed to explore, take multiple passes at an assignment, and be as detail-oriented as the project deserved.

As you can see in the example below, we ended up with more of a pantomime of what a human expects a cat to be thinking rather than realism. But it feels closer to the real thing. It’s been incredibly lovely to experience the positive reaction players have had to Kitty’s antics. We got there not just by portraying cats, but by portraying cats as we see them, through the lens of our high regard for these incredible little creatures.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)