Creating a prequel story to a historical figure's works in The Forest Cathedral

Brian Wilson discusses the thought processes that went into creating a surreal mixture of 3D forest exploration and brutal 2D platforming, as well as how those connect to a book on DDT by Rachel Carson.

The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

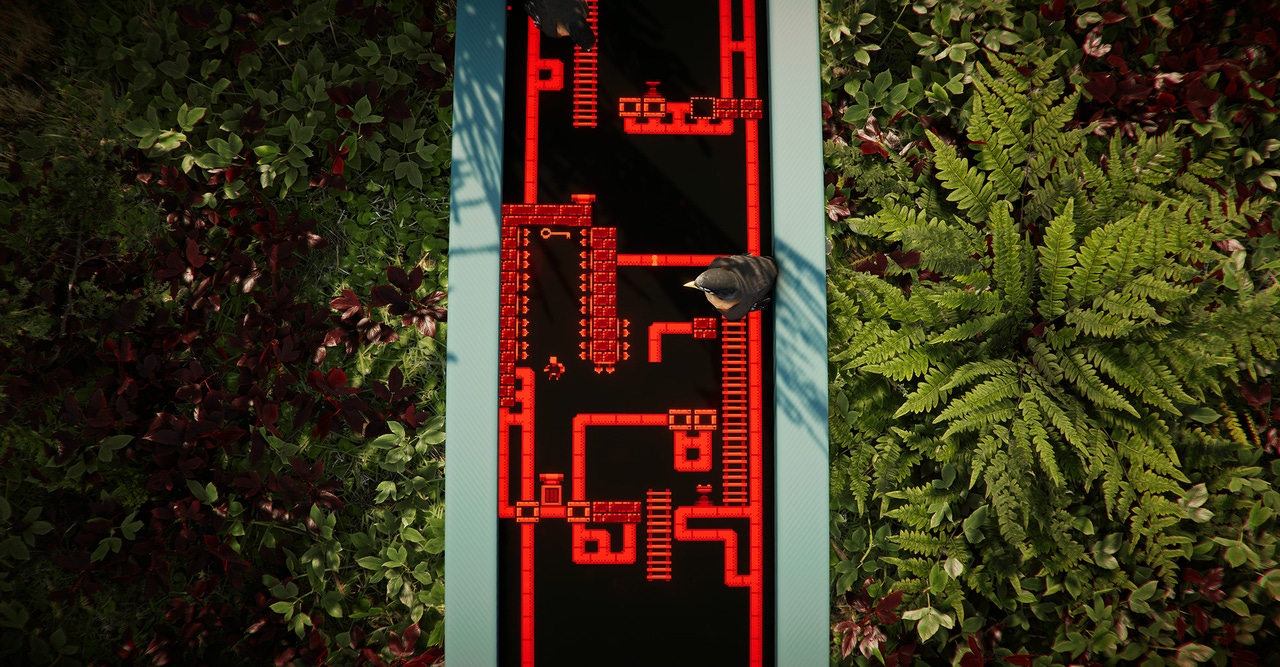

The Forest Cathedral is a surreal exploration of historical figure Rachel Carson and her research into DDT, told through a mixture of platforming and forest exploration.

Game Developer caught up with Brian Wilson, developer of this Nuovo Award-nominated experience, to talk about making Carson’s research and information on DDT more easy to comprehend to a player who's unfamiliar with it, how challenging platforming and exploration tied to this story about Carson's work, and how they designed in-game scanner to capture the invisible effects of an alarming chemical.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing The Forest Cathedral?

I am Brian Wilson, the creator of The Forest Cathedral. While I was lucky enough to have a small development team and publisher, I was effectively the one who put it all together. I am also the portfolio director at indie publisher Whitethorn Games.

What's your background in making games?

I grew up playing games with my family in the PlayStation 1 era. Games like Crash Bandicoot, Spyro the Dragon, and Tony Hawk resonated with me early on. Casual playing continued throughout high school until podcasts started to become more popular and I learned that there was a deeper discussion to be had about games themselves and the people who made them. That was the first time I even had the thought of attempting to make a game and had no idea where to start.

I had a few rough stabs at downloading some kind of game software at the time, eventually going nowhere and giving up. For whatever reason, I’d come back to the idea of making something each year, gaining a tiny bit more knowledge every time I did. I think it’s a lot easier to get started now, but I want to stress this was not the case in 2013.

I had been building my creative toolbox with my love of photography, video editing, and music. So, adding an interactive wrapper to the rest of my skills was very much of interest to me. Unfortunately, that was shelved until 2015. At this point, I was a broke college dropout working in a shoebox-sized coffee shop. I was at my creative peak but ultimately unfulfilled with just still images.

One gloomy day at the coffee shop, the algorithm Gods must’ve been reading my mind (or Google searches) and delivered me the newest programs at the local community college. Across my phone read Multimedia Programming, Simulation & Gaming—I couldn’t have tapped the link faster. Scouring the curriculum up and down, I was thinking to myself “This is awesome, but what the hell is Maya?” The degree was brand new and starting that fall. I applied immediately.

I was able to cut my teeth in game development through programming, animation, design, audio, and art classes. Despite not excelling in school, especially in math, I did quite well academically in this stream. Leading up to our final semester, our final project was supposed to be using Unity to make a VR game. With VR being a hot topic at the time, this was a huge deal. Long story short, that class almost got canceled because there were only three of us students, and four were needed, so it got changed into another animation class. This was a heart-breaker because I still had more to prove, but it dawned on me that I could download Unity on my own computer… and do it myself.

So that’s what I did for the rest of the semester, developing my own game which was called Where the Bees Make Honey. Bees, for short, is how I met my current publisher and now employer, Whitethorn Games. Ultimately, it’s what led to my follow-up title, The Forest Cathedral. And it’s the reason why I’m writing this now.

Images via Whitethorn Games

How did you come up with the concept for The Forest Cathedral?

I definitely didn’t get there in one go. The end result came from different compounding ideas that evolved over the course of the development of Where the Bees Make Honey. The main concept of the game came from the idea of controlling something on a screen from a distance, whether that be a computer or TV. A good example is if there was an old TV in an alleyway on the ground, but the camera is backed up, and you can see the brick wall and ground around it. There was something about that visual that interested me. I kept coming back to the idea of a 2D platformer in a dynamic 3D world. Everything else came after. I knew I’d see it through if I was interested enough in my core mechanic.

What development tools were used to build your game?

I used Unity at the core of the project with PlayMaker making all my scripting possible. I used Ableton Live for music and sound design and Photoshop for anything 2D-related. There are more plugins within the project, but I really tried to keep this one clean. A cool mood board tool I used was PureRef, allowing me to group visual references together.

What interested you about exploring the story of Rachel Carson and her research into DDT?

In college, I was taking an environmental science class focusing on subjects like invasive species and notable people local to us in Western Pennsylvania. It’s here where I learned about Rachel Carson and her most popular book, Silent Spring. The fact that we both grew up near Pittsburgh interested me enough to look into her story more. Plus, the concept of the next game is always more interesting than what you’re currently making. I thought Rachel and Silent Spring were only going to be a small inspiration for whatever I was going to make next, but the more I researched, the more I realized the story deserved its own game.

What research did you do for the game? How did it shape what The Forest Cathedral would become?

The most obvious first step was to read Silent Spring, which was published in 1962. The goal of the book was to call attention to the dangers of a pesticide called DDT, which was used during WW2 against mosquitoes to stop the spread of malaria. It worked well, but almost too well. Carson’s approachable writing style was a threat to giant chemical companies, which got the attention of U.S. President John F. Kennedy.

After reading Silent Spring, I was able to find a ton of great resources on Rachel, Silent Spring, and DDT individually. From there, I sort of built my knowledge toolbox and created my own story inspired by what I learned.

Images via Whitethorn Games

What thoughts went into turning Carson's story into a video game? How did you shape her story into The Forest Cathedral?

I knew from the beginning that I didn’t want to make a one-to-one retelling. That story already exists and is great, plus it wouldn’t abide by the surreal world I wanted to create. But I wanted to keep some key elements and versions of “true events” in my version. I think about The Forest Cathedral as an inspired prequel to Silent Spring. So, with that, my main focus was getting the scientific facts about DDT and its effects correct. I’m not a scientist, so I needed to break down that scientific information in an easy-to-understand way. On top of that, and equally as important, I had to make sure everything blended together and made sense in the world I created.

That being said, because the narrative in the game is its own unique story, players won’t feel left out if they haven’t read Silent Spring or don’t know who Rachel Carson is. I aimed to respect her story but fictionalize it in different ways to make sure it’s engaging and interesting to players.

How did you design the 2D platforming segments in the game? What ideas went into designing these challenging single-color platforming segments?

Luckily, during the brainstorming stage I was able to sketch out level ideas on graph paper. Again, the idea of a dynamic 2D platformer is what started it all, so I had ideas that did eventually make their way into the game years before implementing them. It was a mix of sketching those ideas out and then making sure they fit into the world within the story.

Throughout the game’s main world, Science Island, there are interactive computer terminals. Each terminal holds a specific and important purpose and so does the platforming inside of it. This was truly the most difficult part of development because each terminal was unique in every way and couldn’t be duplicated other than the 3D model itself.

One of my biggest accomplishments was figuring out how to actually put the 2D platforming sections inside of the 3D terminals. I don’t think it was the most optimal way to do it, but I’ll just say using render textures saved my life.

I wanted each level to serve a purpose, connect with the story, and do something new. So, it was a back-and-forth between 2D interactions affecting the 3D world and vice-versa. While studying human-computer interaction, I was greatly inspired by the invisible gorilla experiment. A very popular experiment highlighting inattentional blindness. I wanted to capture this in the 2D sections; when players would be so focused on platforming, what could I incorporate into the backgrounds, and how far could I push that?

Why did platforming levels feel like they suited this story and the feelings you were trying to evoke? What inspired you to use them in this game?

It’s an interesting combination for sure, but I’ve always made weird games, so it made sense to me. The Forest Cathedral is a game of contrasts, so blood-red, pixelated, hard-as-nails platforming pairs well with the first-person walking-sim.

When starting the game I set myself up in a way that if I didn’t receive any funding or help, I actually could finish the game. Luckily, my programmer, Phoebe Shalloway, did amazing work on the game. The platforming was a great fit because it’s a genre I truly love and wanted to play more of. Unity’s tilemap editor allowed me to quickly make and test levels as well. I felt like I had a lot of creative freedom with platforming because it’s more than just the jumps, dashes, and wall-climbs involved. There was voice acting, the 2D character you control called the Little Man, sound design, tense moments, and, above all else, a fun way for me to connect video games and science.

Images via Whitethorn Games

How did you create the forest and places players would explore throughout their time with The Forest Cathedral? How did you design this sprawling place?

Science Island. Broken up into quadrants? Ties into the story. More I could’ve done. Just me designing the game so it ultimately had to be something I could finish.

The main area of the game is called Science Island. It’s environmentally based off of Cooksburg, PA, and the coast of Maine. The Forest Cathedral is actually an old-growth area in Cook Forest State Park—home of some of the oldest, tallest trees in the country.

I knew I wanted to start with an island as it draws clear boundaries and provides important story beats for me to go off of. I broke the island up into four quadrants to match the story—mosquitoes, fish, birds, and then humans. The island and forest within it gave me room to scale up and down depending on resources and capabilities.

In terms of tech, I leveraged Unity’s powerful HDRP pipeline and everything that came with it. Giant sprawling trees meant everything, from their wind movements to the creaks and cracks they’d make. Being able to paint foliage throughout the island and have it all dynamically move with the wind brought the world to life.

What drew you to add the scanner tool to the game? Why get players to scan the environment for these distressing bright lines leading them around?

At first, I wanted a camera element in the game, and with my background in photography, I thought that could be really interesting. Like everything else in the game, I didn’t get there in one clean swoop—which ultimately leads to the most interesting results in my opinion. It was a play on the effects of DDT, and, most importantly, being able to see things with it that aren’t in the “real world.” That multifunctionality allowed me to gamify it and use it for navigational and interactive purposes. I'm really just trying to do a lot with a little, and dive deep into the few systems I had and see how far I could go.

Making a game is so obviously difficult, and you test your game over and over and over. I knew I had something to keep with the scanner because it excited and surprised me every time. You need moments like that to cross the finish line.

The Forest Cathedral is a unique take on a historical figure, feeling less like a direct retelling of their story that most games on important figures would do. What were you striving to make the player feel with this experience? What were you trying to evoke with this game that was connected to Carson's experience with researching DDT?

My main goal was to raise awareness about Rachel Carson, her story, and Silent Spring. My best ability to do so was through a video game, which added an entirely new perspective. In terms of feeling, we tout the game as an environmental thriller, so there’s a general unease laced throughout the game. No matter how beautiful the forest looks, there’s just something off. The game was originally supposed to be a lot darker, thematically, before turning into what it is now. So, the spookier elements came into the beautiful world and created a nice contrast. I kept saying, this is scary because it’s real.

My biggest hope is that players will become interested in Carson’s story and pick up Silent Spring, research her life and career, and use this as motivation to look deeper into the effect she had on humanity’s impact on the environment.

My biggest hope is that people from the science community will check the game out, and then other indie games. The same is true for players to, hopefully, read more into science and the effects humanity has on the natural world. In the end, if players can take away one piece of scientific information that they learned through the game, then I achieved my goal.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)