Behind the HONK: An Untitled Goose Game Q&A

Everyone seems to be honking a bit more than usual with the recent release of House House's brilliant Untitled Goose Game. We speak with programmer Nico Disseldorp.

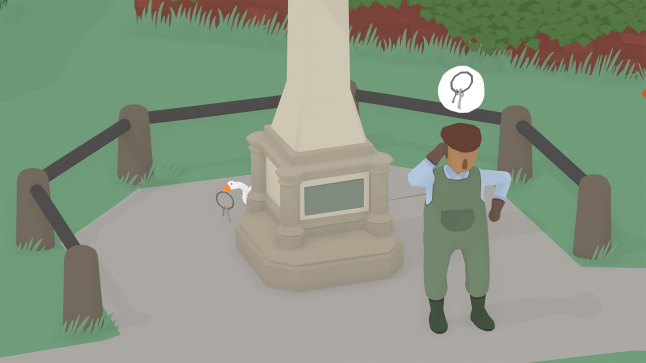

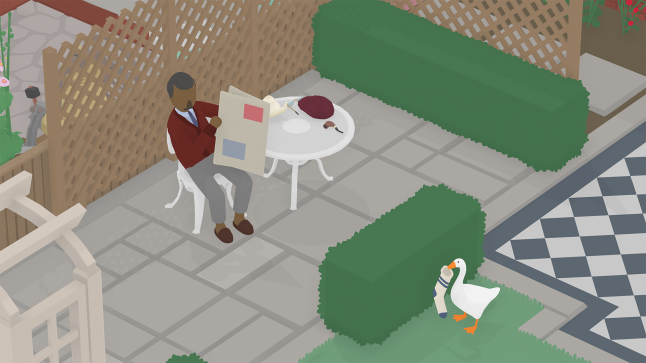

Everyone seems to be honking a bit more than usual with the recent release of House House's brilliant Untitled Goose Game, a game where you take control of a horrible goose who terrorizes the unwitting members of a small town.

House House's Nico Disseldorp, programmer on the game, recently answered our goose-related questions.

Gamasutra: Who are you, what is House House, and what is Untitled Goose Game?

Nico Disseldorp: House House is four people; Nico Disseldorp (me), Michael McMaster, Jake Strasser and Stuart Gillespie-Cook. While we each have specialties in terms of the day to day work we do (I’m the programmer) I would say the more important part of our job is the bit where talk everything through together. Everything is decided by consensus, so the four of us choose together how the game comes out.

The four of us were friends before we had ever made video games, and we started making our first game Push Me Pull You because it sounded like a good way to spend some time together. That game caught a few people’s attention and things very slowly snowballed and we eventually became a video game company.

This goose game is one where you play as a horrible goose who tries to ruin everyone’s day. The game started with that premise, and we just kept trying to think of funny things for a goose to do, and funny ways for people to react, until eventually a game started to solidify around the idea.

Untitled Goose Game was made by more than just the four of us. We also worked with Em Halberstadt, who was the sound designer, Kalonica Quigley, who did additional art and animation work, Dan Golding, who made the music and Cherie Davison, who programmed the rebindable controls.

Gamasutra: Untitled Goose Game first hit the scene nearly two years ago, in a memorable YouTube video that got passed around a number of sites. How useful has been social media in publicizing and promoting the game?

Disseldorp: That video was made by Jake, who is also one of the developers. He has a background in film and TV, so trailer work comes pretty naturally to him. The video itself was thrown together quite quickly with a bit of an assumption that not many people would see it. In hindsight I think “not overthinking it” probably helped the video in a few different ways.

After we posted the video online it was quite popular, and something strange happened where places were reposting it more like it was from the “funny video” category rather than the “game trailer” category. Maybe the fact that the game didn’t have a name helped? The video’s big success was a surprise to us and definitely changed our perception of the game we were making.

Our general social media strategy is to avoid thinking about social media as much as possible. We want to stay focused on making the game. But we know that Jake is good at making videos, so we generally try to ignore social media day to day, until we have something to say, like a platform or release date announcement, and then do a video about it.

Despite often feeling like we should tweet more, I think this has worked out pretty well for us. Once someone told me they really liked how “mysterious” our social media presence was, which seemed very generous. I would have said “inattentive.”

Gamasutra: The tone of the game is remarkable. No one speaks, but their mannerisms speak volumes about what they're like. What inspired this little bubble of life? Were you worried about making a more low-key kind of humorous game? Was there any temptation to make it a bit broader?

Disseldorp: The whole idea for the game started with this realization that a person having to interact with a scary goose was this very normal, grounded conflict. Getting chased by a goose is absurd, but it really does happen to people all the time. So for us the mundaneness, or everydayness of the situation was very important.

Every now and then during development we’d come up with an idea for something bigger, like mucking up a wedding for example, but we’d always let those ideas go because we wanted to make sure that it felt like this was a very normal day in the character’s lives. Anything out of the ordinary is the result of the goose.

I guess this aversion to escalation also helps with the structure of the game we wanted. The human characters are able to tidy up most messes and put things back to normal again, giving the goose a chance to play the same tricks over and over. The mischief is a bit cyclical.

Gamasutra: Each character has the things they care about, and their way of reacting when those things are upset. How did you create and refine this emergent gameplay? How much iteration did you do upon it, and how did it change through development? And when did you realize that the game was really funny, and how did you isolate and refine the humor?

Disseldorp: We didn’t have too much of an up front plan about how all this stuff would work. In that sense it was very iterative. We started with the premise “you are a horrible goose” and some vague ideas like “the goose could steal stuff from people” that sounded like they might be funny, and then had to work backwards and add systems that could support the moments we wanted.

We did this by making a single AI character (the precursor of our groundskeeper) and just slowly adding behavior that felt like it could contribute to the situations we wanted. One of the first things we did was give them a few items that the goose could steal, and made it so they would chase after the goose to get them back. At this point we didn’t have any sense of the game’s wider game progression or if there would be any goals, we just kept trying to add things the would make stealing things feel better.

Eventually this led us to add idle loops where people would use their items, reaction animations for state transitions, vision cones, remembered positions, thought bubbles. In hindsight obviously lots of these things took inspiration from stealth games, but we picked them up one at a time just because they seemed right for the kind of small scale interactions we wanted.

Gamasutra: It's not been remarked upon much so far, but those who pay attention will note it: the interactive musical accompaniment is amazing. It has what I think is the best procedural soundtrack I've ever heard...How [the soundtrack] adapts to the current situation; how it'll delay beats in search of the perfect time to add a note of punctuation; how it'll sometimes seem triumphant when the goose pulls off the heist of some knickknack; how the themes of different characters will start playing as you change areas; and so on. What else can it do, and how did you manage to accomplish all this? Is a soundtrack in the offing?

Disseldorp: The story of the game’s music started when early on we realized that we liked how the game felt alongside these old solo piano pieces from Debussy’s Preludes. They reminded us of silent films or “micky-mousing” in cartoons, but were a bit softer, and conveniently these compositions were in the public domain, so we were allowed to use them.

We decided to use Debussy as some trailer music, and asked Dan Golding (who did the music for Push Me Pull You as well) if he could make us a new recording for the trailer. That trailer turned out to be very popular, and one thing that people kept remarking on was how much they liked the “reactive” music. This was a misunderstanding and the music was not reactive (we had cut the trailer to the music and not the other way around) but there was something about the way that particular track jumped around with disjointed phrases that really let people believe the music was reactive.

Optimistically (and perhaps naively) this made us wonder if we could maybe just do what people thought we were doing, and play the different parts of the Debussy piece in a disjointed way, reacting to what the player was doing. We figured that if it worked correctly, it could feel like a piano player was accompanying your game session live.

It took us a few different attempts to find a solution that worked, but we ended up with something we are very happy with. The final system has two versions of each track; one that sounds like the original composition, and another “low energy” version that plays in a more subdued way. Dan has split each version into hundreds of different audio files that each represent about two beats of music. Depending on the action on screen, we can then have the music seamlessly move between playing the high or low energy versions, or to pause on silence for a while. At any given moment there are only two possible audio files that could play next, but because there’s lots of room to jump up to a higher energy or down to a lower energy or to silence it’s easy for the game to make a perfectly timed change in energy that feels very deliberate and specific.

There will be a soundtrack (soon hopefully) but there is still a bit to figure out about how it will work. Obviously in the game the music plays differently each time, whereas on a soundtrack there will be one version that’s the same every time. I think Dan has some good ideas about how to do it and I’m looking forward to the end results.

Gamasutra: Examining the old trailer from 2017 shows a few minor differences. One of them is that the game is, subtly, a bit fuller in terms of non-soundtrack music. The quiet "fwap" of the goose's footsteps is new, and the goose's voice is a lot more realistic (before it was kind of a rough quack). I've also noticed that the radios in the game have multiple stations. How important was it to you to get the sound right, and how much of the effort of making the game went into it?

Disseldorp: That old trailer uses placeholder sounds sourced by us from royalty-free online collections.

In 2018 Em Halberstadt come on board and replaced everything with the sounds you hear today. She was extremely thorough and really went overboard finding different places for unique sounds. As just one example, there are maybe 160 or so unique objects in the game, and all of them have unique sounds for being picked up, getting dropped, clanging on concrete, thudding on the grass, getting dragged around on different surfaces. It’s incredible to me. The end result is something very playful, where simply touching everything in the game is kind of a game in itself, just to see what kinds of sounds each object will make.

Gamasutra: Interactions between unexpected things helps keep players coming back a time or two for more after finishing the main course. Although I was a bit sad that you couldn't get the old man to wear the groundskeeper's hat (yes, I tried), I was pleased to find that hiding in the box in the Neat Neighbor's yard resulted in getting thrown over the fence! Many of these things are highlighted with items on the game-end to-do list.

Were all of these things ultimately planned, or did a few interactions emerge from the properties of the items? Were you yourselves surprised by any interactions? Are there any special interactions you'd like to draw attention to?

Disseldorp: These types of things were a mix between systemic stuff that worked for everything once it was set up and lots of handcrafted solutions where we tried to anticipate what else people might try, or might believe would work. We’ve been happy to keep the boundaries between the two pretty vague, so it’s not always obvious to a player what’s “core behavior” and what is more handcrafted.

Filling in edge cases where something felt like it “should” work was important to keep people believing in things they wanted to try. Our whole game relies on people believing that their silly ideas might just work, so if we had a rule like “you can steal someone’s slippers when their feet are off the ground,” then we had to find other situations where the slippers were off the ground and make the slippers steal-able then as well.

I don’t think we added many things specifically for the post-credits to-do lists. Our approach to them was just to think of interesting things you could already do in the game and just write them down.

Now that people are playing the game at home, some things have definitely surprised us. We’ve watched a few videos or streams in the last week and said “I didn’t know you could do that” after someone breaks the broom by tug of warring with a different character or something.

At the same time, we knew we could never cover every possibility, some things players might want might not work for technical reasons, or we didn’t have the time to make them work in that way. So we had to signal to players that some stuff won’t work as well. For example, one of the first objects you come across in the game is a bright red lawn mower that looks like it could be turned on. We never ended up adding interactions for it, but left it in the level because we found that it was a nice way to calibrate expectations. In this game lots of stuff will work, but some stuff won’t and that’s okay.

Gamasutra: It seems, to me, that a lot of Untitled Goose Game's charm and fun comes from the unwieldiness of the goose itself...Yet the goose controls well; it's the perfect mix of awkward and capable, and despite how flexible and adaptable its model is, it always looks and feels, not like a model, but like a natural, realistic goose, which makes a couple of the extra objectives, like "Score a goal," a lot trickier. How did you model the goose's appearance and control?

Disseldorp: Controlling the goose requires a bit more active attention to low-level things like reaching and moving than in lots of comparable games. I find this type of complexity does a lot to shift the scale of the interactions towards a smaller scale. Things that might be so trivial as to not be worth mentioning in some games, like “walk over there and pick up that item” are made slightly more physical and interesting. It’s enough that you could say someone did a good job or a bad job of it.

The extreme of this type of small scale movement focus is a game like QWOP, where movement is nearly impossible and to walk at all is a huge accomplishment. For the goose I think we try to use that same ingredient but just add the tiniest bit. It’s like 1 percent QWOP.

To make a bit of a broader claim, I think this is about avoiding artifice. In lots of games movement is assumed to be trivial, and the challenge comes from something more genre-based, like shooting or jumping or whatever. But those things can lead to a game where the character seems really natural most of the time but then has to kill a hundred people and jump over heaps of boxes for some reason. One way to avoid this is to make a game without that kind of challenge, like a walking simulator, and for us we tried to put the challenge into other places. So we have slightly more complex movement, more obtuse clues, that sort of thing.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)