VIDEOVERSE imbues young love with vintage social interface style

Embracing old platforms like MSN Messenger and Miiverse gave the story a romantic momentum and distinct visual flair.

VIDEOVERSE is a love story set in the world of 2003 computers and gaming consoles. Set in chat rooms and message boards inspired by MSN Messenger and Miiverse, players follow the story of a relationship while trying to keep up with their friends (and foes) online.

Game Developer spoke with Lucy Blundell, the game’s creator, about the interesting design and cost benefits that came up from creating a game around an older computer interface, how this interface style affects the cast of the story, and how creating a fictional gaming system formed an important early moment for the game’s creation.

What inspired you to couch your newest narrative game in this particular era of internet forums and console chats? What appealed to you about telling a story within this framework?

There were a few things, really. The main reason was that I wanted to tell a story about online teenage friendships as I was about the same age as the main characters in the year VIDEOVERSE is set (2003). I remember excitedly logging on to MSN Messenger when I got back from school, checking for any updates on my favorite message boards, and caring for my beloved Neopets. It was a heartwarming time for many, so I wanted to revisit some of those memories.

I’d also played a lot of, what I like to call, “interface games”, or games set in computer simulations. For the IGF narrative jury, I’d played Do Not Feed The Monkeys, Hypnospace Outlaw, and STAY, in addition to a few others. It felt like these games kept popping up in front of me, so I wanted to try my take on them, focussing more on the online relationships instead.

What challenges or benefits came from telling a story with this chat and messageboard-styled format?

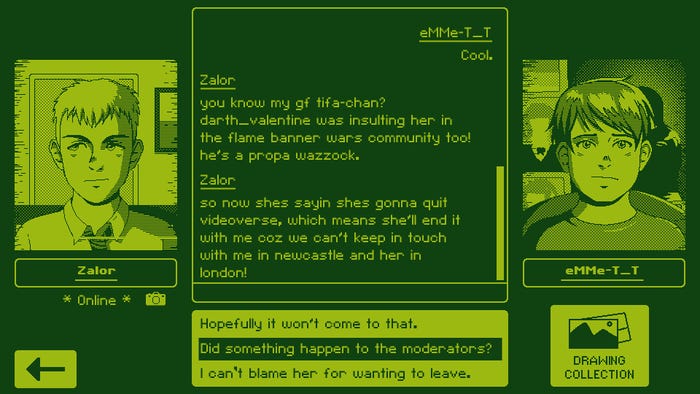

Since I wanted to focus on character, I actually had no idea how to effectively show Emmett’s (the protagonist) thoughts whilst he’s browsing the Videoverse gaming network. Initially, I thought I’d completely cut away and show him infrequently, but when testing the game, it felt like he needed to be more involved and help steer the player in the right direction. Then I tried a popup in the middle of the screen, but it felt robotic and impersonal. It seems obvious now, but having his thoughts and expression appear in the bottom right corner took me longer to figure out than it should have!

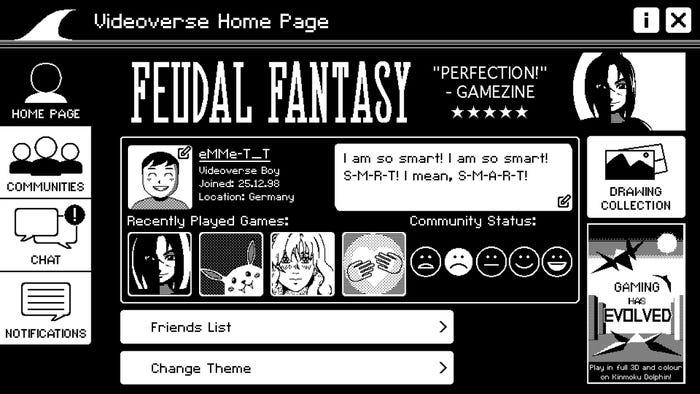

The biggest benefit of telling a story in a computer interface like this is the immersion—after all, these programs are all played on similar devices themselves, so it has the potential to feel extremely real. Another benefit to this format is that I was able to populate the online world more easily. Here, a character is mostly just a profile picture, nickname, and biography. I didn’t need to design a 3D model or hire a voice actor to bring a character to life so, as a sole game developer on a budget, this worked for me.

Did this style affect the creation of the story? Did the story shape the messageboard framework of the game? How so?

Originally, I wanted to tell an online love story between a teenage boy and girl—something simple and sweet. Although Emmett can be played romantically or platonically, kind or cocky, it is a love story at its core. However, because of the setting, it didn’t feel right for there to be only two characters to focus on—I needed to populate a fake social gaming network and ensure it felt real. So I added more characters—some who support Emmett, and some whom Emmett supports.

There are also a bunch of randoms who have very little to do with the main story but exist to fill the world and give players a laugh at the real randomness of the internet. Some of these characters focus more on drawing silly pictures, whilst others like to troll and bully. To feel worthwhile, all these extras needed to be followed up; what should happen to the trolls if they’re harassing someone? Can they be reported? Is it immoral to “like” a drawing if it’s inappropriate? Stuff like that.

By the end, the side stories and world-building became as important, if not more so, as the main story. Everyone has their own drama going on in Videoverse…even Videoverse itself!

Sucking (inter)face

VIDEOVERSE feels like it captures a specific era online, but also like it captures a specific way of carrying oneself online in the earlier days of the internet. What thoughts went into imitating that tone and feel with the dialogue and characters? How did you bring players back to that era through how your characters "spoke" and wrote?

I tried my best to remember how me and my friends used to interact back then. People had more time for each other and were less distracted than today. They also used older memes, “smileys” and phrases long since forgotten. The book “Because Internet” by Gretchen McCulloch really helped me with the writing, but one of my unfinished projects (which I started writing nearly a decade ago!) was also set in a similar online era. I’m very much terminally online, which no doubt helps in writing such a story!

What thoughts went into creating the visual style of the forums, chats, and consoles the player would explore? What felt important to bring to the visuals to capture the look and feel of that time online in the early 2000s?

At first glance, VIDEOVERSE has a strange art style for a computer interface in 2003. However, the whole game was initially inspired by Miiverse drawings, which are 1-bit black and white. World of Horror, Minit, and the visual novel segments in Travis Strikes Again: No More Heroes are games that have this style and I found myself transfixed by them. 1-bit also felt in the scope of a sole developer, which is something that’s always at the back of my mind—can I actually achieve this by myself? I knew VIDEOVERSE would require a lot of drawings, characters, animations, and adverts, so I went ahead with it.

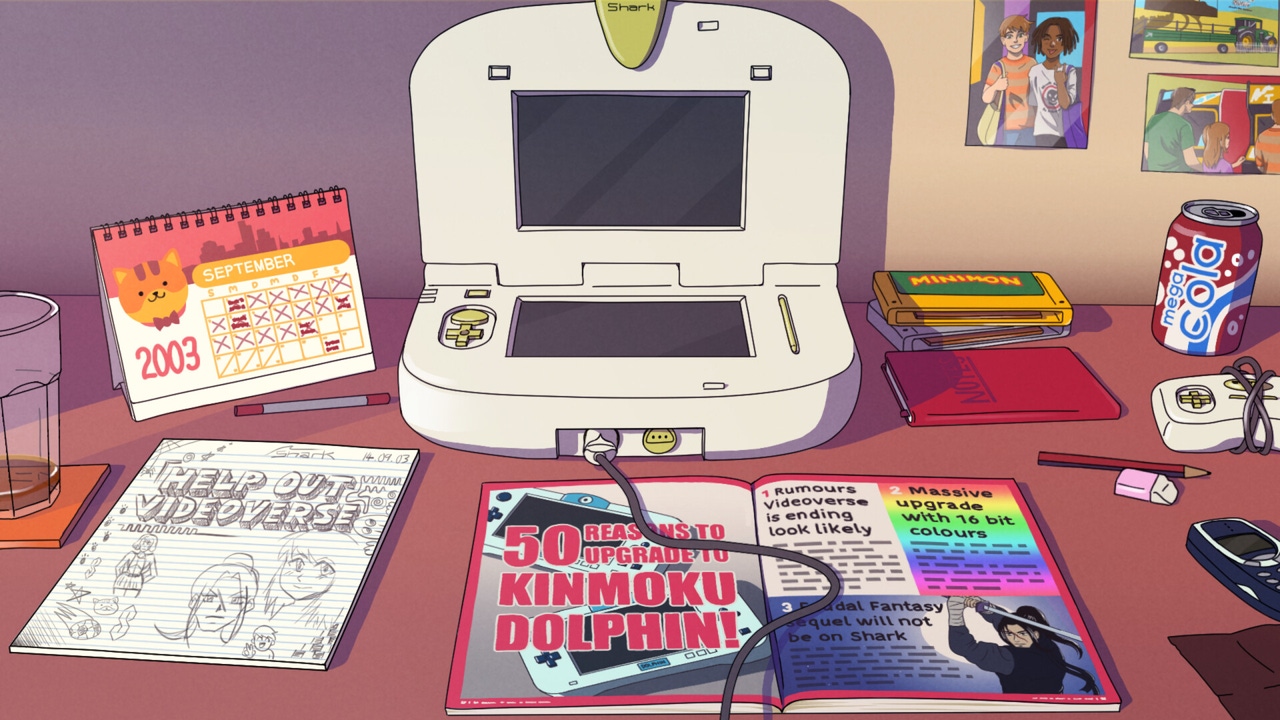

Also, I’m generally fed up with the notion in gaming that “advancement=graphical realism.” I prefer to look at video game consoles the way Nintendo does, where functionality is higher priority than graphics. For the year when the fictional “Kinmoku Shark” console released (1998), it’s not too dissimilar to a Gameboy or Nintendo DS—It has two screens, a touchpad and stylus, and an ethernet port. Despite the 1-bit graphics, I think it’s a pretty cool video game console!

As for the real-life segments of the game, I wanted them to feel “washed out Y2K”, with objects dotted around to reflect the early 2000s, such as game cartridges, a Tamagotchi, and a Nokia 3310.

The Kinmoku Shark console and the Feudal Fantasy game are core pieces of the experience. What ideas went into creating these separate, but important, elements of the game and its story?

For the Kinmoku Shark, I wrote a special blog for Game Developer, which you can read here.

For Feudal Fantasy, I’m a big fan of Japan, anime, manga, and, obviously, Final Fantasy. The characters needed to bond over something they love, so a Final Fantasy knockoff JRPG suited, as lots of people can relate to it.

Japanese folklore contains a huge number of fantastical creatures, such as Kappa, Oni, and Inugami, and I thought they could make cool enemies in a fictional video game (which are seen as fan art in Videoverse).

I don’t claim to know too much about the history of Feudal Japan, but there’s a lot of weight behind some of the characters you see in the Feudal Fantasy cut-scenes, such as Oda Nobunaga, Akechi Mitsuhide, and Hattori Hanzo—the latter rumored to have supernatural powers due to his incredible skill. If you know a bit of their histories, it makes the story of this fake game all the more exciting.

Why were a console and game important to forming the background of this chat-based universe and this particular period?

I didn’t want to tell a social media or computer simulation story since a few of those exist already. What I really wanted to do was tell a story of the last days of a social gaming network. It’s specific and, due to the nature of video games, more passionate.

To succeed, there needed to be a game that the player also felt invested in just like Emmett. Whilst Feudal Fantasy is meant to evoke feelings of similar games, the player can make their own thoughts about it through watching the cut-scenes. Since the majority of the game is set in Videoverse, with few colors and animations, the flashy, over-the-top cut scenes felt like a fun way to take a breather.

Sound effects and music feel like vital pieces in getting into the mental space of VIDEOVERSE. Can you tell us about what you wanted from the sound design of the game? What made it feel like it brought everything together?

Clark Aboud and Alexandre Carvalho helped create the Kinmoku Shark’s sound system. The audio needed to evoke the late '90s/early '00s and sound as though it was really coming out of the console’s sound chip. The button clicks and startup sounds were actually some of the first things that were added to the game, even before the majority of the story was written. This helped me while I was testing, as it gave me a feel for the fictional gaming system and what was/wasn’t working.

Did the experience of working on your previous game, One Night Stand, affect the design of this title in any way? How so, or how not?

I was always surprised at how big One Night Stand got when, for me, it was a random idea for a game jam with little of my own experience in it. However, VIDEOVERSE is the opposite, with a lot of myself in it. Perhaps too much! I really wanted to see what I was capable of if I played to my strengths instead.

However, if you’ve played both games, I think it’s easy to tell they’re made by the same developer. I love focusing on deep one-on-one conversations rich in awkwardness and empathy.

What thoughts, feelings, and memories came up while working on the game? Did re-exploring this time stir up anything within you?

While making VIDEOVERSE, I surrounded myself with a lot of things from around that era. I watched old anime, played with an original Tamagotchi again, and read old gaming magazines and books. Somehow, the TikTok and YouTube algorithms cottoned on and kept suggesting videos that helped me remember things from yesteryear even more.

Developing VIDEOVERSE made me feel a little sad for the way the internet has become more ad-driven, pay-to-win, and subscription-based. Previously-loved communities have either changed so much they’ve lost their original purpose, or they’ve been abandoned. However, as someone who makes a living selling digital games online, I’m also grateful for the opportunities the internet can still bring.

VIDEOVERSE’s development actually started in April 2020, near the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. I also became disabled in 2019, and this, plus the pandemic, got me thinking a lot more about how important online communication is when the world is no longer accessible. Developing VIDEOVERSE was cathartic for me—I cried a lot, I laughed a lot, and I took a lot of pleasure in looking back on simpler, joyful times. I hope playing it evokes similar feelings for others!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)